By Moira Cue

On view now through May 6, 2012, the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art presents, "In Wonderland: The Surrealist Adventures of Women Artists in Mexico and the United States." I recommend going early or purchasing tickets in advance, because this exhibit was nearly as packed as the crowd-pleasing "King Tut" exhibit a few years ago. So if you suffer from claustrophobia, you've been forewarned, but it's still worth the minor inconvenience of being packed in like sardines to see this show. "I heard this was the Frida Kahlo exhibit," I overheard one patron remark to another. While Kahlo is arguably the most famous female surrealist and, some say, one of the greatest artists of all time, Kahlo is far from being the only major artist shown here. Dorthea Tanning, who passed away this month in her ninety-eighth year, as well as Louise Bourgeois (who I never thought of as a Surrealist per say, and whose more well-known works were created decades following the peak of the movement), Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, photographers Lee Miller and Lola Alvarez Bravo, and the perennially underrated filmmaker Maya Deren, whose collaborators included Marcel Duchamp. (It seems Duchamp didn't mind taking direction from a woman.)

According to the exhibition's catalog, "(The Surrealist Movement)...is most often identified with male artists, many of whom objectified women in their paintings, casting them as sexual or symbolic ideals. Conversely, the female artists of the movement delved primarily into their own subconscious and dreams." I admit, I have mixed feelings about this premise--Like Morgan Freeman, who asks why "Black History Month" is necessary, I feel a sense of righteous,albiet muted, indignation over the remedial nature of retroactively inclusive efforts. The statement also fails to explain who is identifying Surrealism with male artists. Is this due to historic or continued biases? Sometimes, if not most always, these groupings are cemented by others not associated directly with the prime historic group of core artists.True, we all know of Salvador Dali's famous clocks, and Magritte's pipe ("Ceci n'est pas une pipe," which was 'not a pipe'). But the women in this group won highly coveted accolades, exhibited and were collected in museums internationally, and moreover lived as and considered themselves no less than the peers of these and many other famous men of the era, throughout their lives. The collective market price for work in this show is in the multi-million dollar ballpark.

Most importantly, there is so much to celebrate about this group of work by extraordinary women. The show's biggest selling point to any Kahlo devotee, like a woman I saw in a wheelchair who looked like she could be a thirty-something granddaughter of one of Kahlo's portrait subjects, Dona Rosita Morillo, wearing the artist's image around her neck and clutching it with the religious fervor of a rosary, is that they aren't just exhibiting an amazing group collection, but the Kahlo paintings on view represent some of her most iconic, memorable paintings, including, The Two Fridas, The Suicide of Dorothy Hale, and the delicately collaged, My Dress Hangs There. Unlike viewing these images in print or via the Internet, the stroke and detail are fully visible. You can squint, for example, underneath the legs and shadow of the lifeless Ms. Hale, and see the pentimento--almost make out the letters--of a previous inscription which has been blotted out and painted over. Standing in front of the double self-portrait, her first large painting and one of her rare works on canvass (she seems to have preferred masonite), you can see how the paint in the collar area on her white wedding dress has been built up through repetitive layers suggesting a struggle to get the outline of the form "just right." And you can see another painterly battle between the 'white Frida's' exposed breast and heart, as well as the photographic realism in the pendant held by her native double. Kahlo's smallest painting; a miniature self-portrait dedicated to one of her lovers in her later years, made headlines in 2011, when it was expected to fetch as much as 1.2 million dollars at Sotheby's last spring.

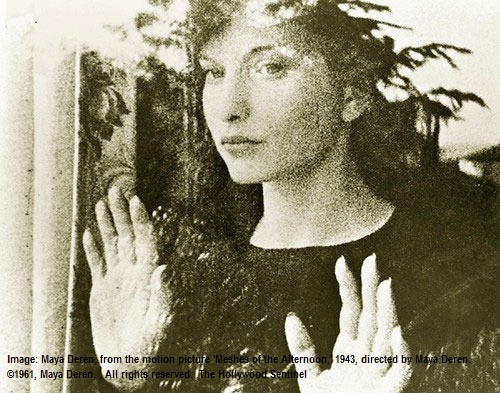

Another extraordinary work to be sure not to miss is The Witches' Cradle, a short, and purportedly unfinished, experimental / avant-garde film by a Ukranian emigrant to the U.S., Maya Deren, which stars Marcel Duchamp and a rope locked in a noirish death dance that emanates a sense of not only dread, but mirth. Deren, born Eleanora Derenkowsky, was the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship whose later work in Haiti documented the rituals of Voudon, and is said by scholarly practitioners to be one of the rare, accurate portrayals of their religion. Like Kahlo, if not more so, she was known for her seductive beauty. Perhaps Hollywood will someday forgive Deren for her invective toward the studio system and embrace her as a fascinating and worthy biopic subject--which she certainly is.

Another emigrant, from Spain to Mexico, the painter Remedios Varo, part of the international, party-fueled Mexico City scene in the 1940s and 50s, created feathery, precise, almost hallucinatory worlds inhabited by vegetarian vampires with V-shaped faces and interior landscapes sharing an architectural logic with MC Escher (i.e. an irrational fantasy). This intriguing and brilliant artist is loved today by members of the animal rights and anarchist communities as a historical genius they can claim as their own: Varo was a lifelong vegetarian and anarchist. Her work has sold for over a half million dollars for one piece.

Kahlo, Deren, and Varo lived intense, tumultuous lives that were all too brief. Kahlo died at 47, Deren at 44, and Varo at 55. One of the longest surviving female artists associated with Surrealism, Leonora Carrington, who was close to Varo, passed away in May of 2011 at the age of ninety-four. Carrington was also an emigre to Mexico city, but, born in England, she brought with her to this somewhat wild place a sense of restraint evident in the emotionally stoic and geometrically balanced elements of her compositions, which hathe solidity of Bero. Of course, her paintings were still Surrealist, which means that a quiet living room is the backdrop for a flying rocking horse. Such juxtaposition of subconscious sybols is quintessentially Surreal--regardless of the gender of the artist.

Visit the show's website by clicking here.

©2012, The Hollywood Sentinel, Moira Cue.