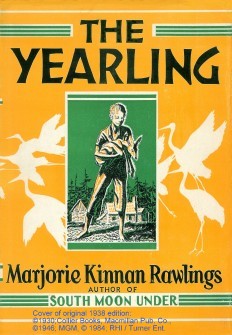

“The Yearling” by Marjorie Kinnan

Rawlings,(400 pages, illustrated by N.C. Wyeth), is the only

Pulitzer Prize winning novel found in the children’s

section of your local library or bookstore. Unlike the novels

about dysfunction and human tragedy, both epic and intimate, of

which there are many, this winner wrote a story about a golden

time, after the Civil War and before electricity and automobiles,

and a young boy, whose idyllic childhood arched through this

time, on an island of long leaf pines in the center of “the

rolling sea that was the scrub” in a sort of endless

halcyon mist. The language that Rawlings uses to describe the

inner and natural world of the protagonist, Jody Baxter, is

euphoric. Here’s an example: “There were other such

islands to the north and west, where some accident of soil or

moisture produced patches of luxuriant growth; even of hammock,

the richest growth of all. Live oaks were here and there; the red

bay and the magnolia; wild cherry and sweet gum; hickory and

holly.”

Jody’s father is a small and energetic, compulsively

honest, son of a preacher named Penny Baxter. Penny was a

nickname given to him because of his size, by one of the meaner,

dark haired Forrester boys, Lem Forrester. The Forresters live

down the street, and have five sons, most of whom are older than

Jody, who is twelve going on thirteen. One of the boys, nicknamed

“Fodderwing,” is Jody’s age. Fodderwing got his

nickname by putting a sod like material on his arms and jumping

off a barn, thinking he would be able to fly. Instead it left him

crippled even further. He was born with a genetic deformity and

is not normal. Fodderwing’s parents let him keep all sorts

of strange pets: a raccoon, black swamp rabbits, and a fox

squirrel. The grown ups consider him “witless” but

Jody appreciates his friend’s gentle nature and special way

with wild animals.

Jody’s mother is Ory Baxter, a large woman usually referred

to as “Ma” who towers over her husband physically.

She won’t allow Jody to have pets like Fodderwing does. She

has a stern, serious nature caused by the heartache of losing

several children as babies or toddlers, before Jody was born. It

is almost as if she is afraid to love him too much, in case he

will be taken from her. Even though she is more emotional than

the men in the story, she is still more stoic than either gender

in today’s world of “touchy-feely”

psychological templates.

The first hint of trouble in paradise comes as Lem Forrester

takes a shining to golden-haired Twink Weatherby. The problem

with that is that Oliver, the son of Grandma Hutto, Jody’s

surrogate grandmother, already believes that Twink is his girl.

The Forrester brothers gang up on Oliver in a fistfight over

Twink, three-to-one, and Penny is called to step in and save

Oliver’s life. Penny and his young son Jody step in on

account of Oliver being unfairly matched. This causes bad blood

between the neighbors, even though Penny tries to explain that it

was on principle that he was forced to step in, and not because

of a personal dislike toward the Forresters. The Forresters feel

that they are the wronged party, which justifies them baiting the

Baxters hogs into traps with plans of changing the brand to their

own.

Penny goes out tracking the hogs, followed by Jody, and says,

referring to the inevitable confrontation over the stolen

property, “When there’s trouble waitin for you, you

jest as good to go meet it,” which is followed in rapid

succession by the irony of being bitten by a rattlesnake. In a

split second, it is up to Jody to save his father, if it is

possible. He tells Jody to run to the Forresters, who are the

next closest human settlement, and get help. A few short moments

later, a doe bounds, and his father shoots, kills, and slices the

deer open, pulling the liver as a life saving antidote to the

snake venom. By placing the organ on a self-inflicted cut over

the bite area, Penny’s father is able to draw some of the

venom out, into the liver. The doe’s fawn walks out of the

brush and cries by his dead mother.

Jody runs to the Forresters,

and cries that his father is dying of snake bite, and begs them

to get the Doctor. Lem is the only one of the Forrester brothers

who is mean enough that he doesn’t care. The other

brothers, Buck and Mill-wheel, after hearing that Penny used the

deer liver, decide that since he has a chance of survival, and

since snakebite is a tortuous death, that they were obliged to

help even an enemy. Buck rides to pick up Penny, and Mill-wheel

rides to get Doc Wilson, who is, like the Forresters, a heavy

drinker, drunk more often than not. Jody can only walk home and

wait at his father’s bedside. On the trip home, he

discovers the reason the doe had leapt out in front of them-to

lead them away from her fawn, who was hiding completely still in

the long grass.

After a long vigil, Penny Baxter survives the snakebite. In an

exulted moment of act of gratitude for the doe’s sacrifice,

Jody’s wish is granted: to find the fawn and bring it home

and raise it. Ma Baxter, who was set against allowing any pets

considering the scarcity of food, is so gra?eful that Penny is

alive that she doesn’t protest Penny’s gift to Jody.

What follows is a love story between boy and fawn, and a coming

of age story. The next year, Jody raises the fawn, and grows

himself from boy to young boy on the cusp of manhood. The fawn,

also male, grows into a yearling, a very young buck, during the

same time Jody goes from hating girls to hating to see the girl

he “hates” playing hopscotch with another boy.

The

conflict over Twink Weatherby escalates. The rampage of carnage

inflicted by a 300 plus pound bear named “Slewfoot”

because of a missing toe continues until Penny has had enough.

The fawn is a symbol for both the father and the son: For the son

it represents his tenderness, that boyhood still allows.

Penny’s father was stern and never let his son be a boy.

Penny wants to be a better father than his own, and so frequently

covers for Jody with his mother when he wants to run off and

play, avoiding chores. His idea is to let him be young. But the

fawn; who, without a mother, would have died in the wild if it

had not been for Penny’s tenderness, also represents

Penny’s mortality. The snakebite doesn’t kill Penny,

but he isn’t going to live forever. He wants to know that

his son will protect Ory.

Death is there, a hovering threat, an ultimate reality,

inevitable. Many of us as adults forget that as adolescents, we

faced death, daring us to begin our ascendance into adulthood,

assuring us of its ultimate victory. That is the underground

river of the melancholy of puberty; The nascent consciousness

that all that follows youth; our blossoming, will end. Jody

Baxter learns directly, and painfully, the hard lesson of the

wilderness.

“The Yearling,” which won the

Pulitzer Prize for the novel in 1938, is a valuable teaching tool

for children and adults about social and cultural shifts in

American history, giving an account of the ecology and landscape

of a region, central Florida, before many of nature’s

predators indigenous to the area became endangered or extinct. It

also reminds us of the sacrifices of our forbearers, for whom

survival was never a given, and could even be interpreted, in a

postmodern context, as a critique of gender roles. For Jody,

becoming a man, means saying goodbye forever to the tender part

of himself that wanted to rescue a baby deer. Was losing

one’s tender heartedness necessary then, for our ancestors?

Is it now, for us? Reading this book will help you find your

answers to these two important questions.

© Moira Cue for the Hollywood Sentinel 2009 all rights

reserved.